24 Sep 2021

Human mobility patterns influence how we experience income segregation in cities

Income segregation is not just restricted to residential neighborhoods; it is part of the places we visit every day.

In a world of increasing urbanisation, migration, and mobility, cities are becoming the epicenter of our social life. Diverse populations and social cohesion are crucial for sustainable urban development, but cities face rising segregation and inequality. Traditional understanding of income segregation, for example, is based on the geographical distribution of residential households; individual activities are, however, not restricted to residential neighbourhoods, and this points to a different form of income segregation experienced by city residents.

Associate Professor Xiaowen Dong, of the Machine Learning Research Group in the Department of Engineering Science, says “At a time when both physical and social exploration might be limited due to the restrictions imposed by the pandemic, it feels particularly important to understand how simple daily behaviours might affect our experience of economic segregation.”

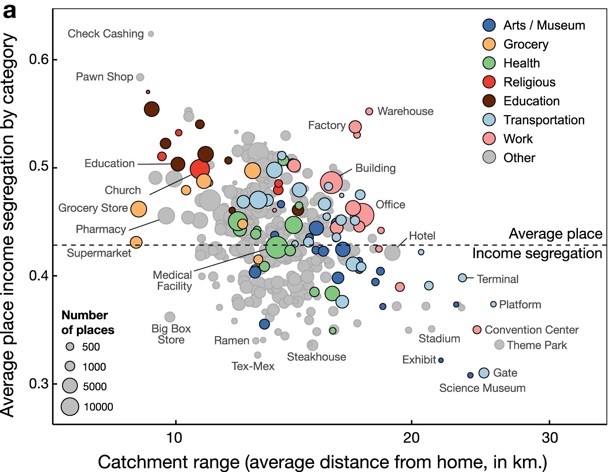

Dong is co-author of a recent paper published in Nature Communications titled ‘Mobility patterns are associated with experienced income segregation in large US cities’. Using anonymous and aggregated human mobility data from eleven metropolitan areas in the United States, researchers at the University of Oxford and Massachusetts Institute of Technology found that income segregation is not just restricted to residential neighbourhoods: the share of visitors from different income groups to amenities in the city, such as restaurants, stores, and other venues, can make those places segregated in their own way. For example, on average, grocery stores and local shops are more segregated by income than museums, art venues, or airports.

There is also a large geographical variability: places with economically diverse visitors can be only a few feet away from those where only one income group is present. “Even two coffee shops across the street can have very different levels of income segregation,” said Professor Esteban Moro (MIT and University Carlos III of Madrid in Spain), lead author of the study.

Different places have different income segregation. The plot shows the average place income segregation by type of place for the eleven urban areas analyzed. Colours correspond to different groups of place types and size is proportional to the number of places in each type. Credit: Esteban Moro/MIT Media Lab (Human Dynamics Group)

The income segregation associated with different places implies that the way people experience income segregation in their daily lives depends not only on where they live but also on their mobility patterns and the places they visit. Combining well-known models of human mobility and segregation, the researchers found that the way people experience income segregation is associated with two different mobility traits.

The first is the tendency to explore new places. In general, “explorers” (people that tend to visit new places more often) experience less income segregation than “returners” (who spend most of their time in a very small set of places). While it might appear at a first glance that this is due to the financial and mobility constraints, the researchers found that the key ingredient to understanding this “place exploration” is individuals’ lifestyles. For example, knowing that an individual visits movie theaters, exhibitions, or coffee shops can tell us more about whether an individual is a place explorer than knowing the income group of the individual.

The second important component is an individual’s tendency to visit places where their income group is not the majority. The researchers found that the tendency of such “social exploration” is not associated with the type of places they visit (their lifestyles), but with their educational level, mode of transportation, or poverty level of the areas where they live. That is, it seems to be more related to demographic and residential characteristics. Hence, the way people experience income segregation in the cities depends on these two relatively independent characteristics.

These findings have implications for our understanding of how income segregation is experienced in cities. In particular, the understanding of urban residential segregation should be complemented with how urban interventions and designs affect where city residents spend time beyond their neighborhoods and with diverse groups of people. Moro concludes, “We have never been so segregated as we were during the lockdowns. The question is, after the reopening, whether our mobility patterns would change to increase the experienced segregation or, on the contrary, we are creating more diverse venues and cities.”

This article is adapted from the original version with kind permission from Prof Esteban Moro Egido and MIT